Jonathan Haidt, the NYU Professor who, with First Amendment firebrand Greg Lukianoff co-authored the explosive Atlantic piece,”The Coddling of the American Mind,” was asked how to prevent another wave of kids on campus who can’t handle reading a disturbing book, or sharing the campus with a visiting speaker whose views contrast with their own. He was interviewed for Firstthings, the journal of religion and public life, by Dominic Bouck, O.P, a Dominican brother of the Province of St. Joseph, in an article titled “Revenge of the Coddled”:

BOUCK: So how do we move forward, out of this vindictive attack culture? Think young.

HAIDT: Children are anti-fragile. They have to have many, many experiences of failure, fear, and being challenged. Then they have to figure out ways to get themselves through it. If you deprive children of those experiences for eighteen years and then send them to college, they cannot cope. They don’t know what to do. The first time a romantic relationship fails or they get a low grade, they are not prepared because they have been rendered fragile by their childhoods. So until we can change childhood in America, we won’t be able to roll this back and make room of open debate.

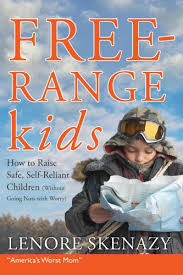

My biggest prescription is that in every hospital delivery room, along with that first set of free diapers, should come the book: Free-Range Kids by Lenore Skenazy. If everyone in America read the book Free-Range Kids the problem would be over in 21 years, when the first set of tougher kids filled our universities.

Ahem. Must “Woo-hoo!” But beyond that, his prescription deserves another moment of reflection. Because, as those of you who have read my book know, it’s not really a “how to parent” book. It’s a, “How did we get so scared about everything our children do/see/eat/hear/watch/try/encounter? And how can we come to recognize that while this worry FEELS instinctive, it is actually ‘normal anxiety’ magnified and twisted by a society bent on shoving fear down our throats?”

So the way to raise resilient kids is to be skeptical about the message we get all the time that they are just moments from doom: An encounter that will haunt them, a loss that will derail them, or an unsupervised couple of minutes that will result in their disappearance. Our society obsesses about the way kids can die in an instant, and ignores the fact that 99.9999% of them won’t, and most of THOSE will emerge no worse (and possibly better) for the wear.

Haidt’s premise is that by avoiding more and more of our “fear triggers” (like, “She’ll die if she goes around the corner without me!”) we give those fears more power. They grow, and so does our kids’ anxiety.

I love safety, but it’s true that once we let our kids do things on their own, the pride and confidence that they feel and that WE feel goes a long way to restoring “normal anxiety” back to its set point, instead of the red alert it is on today, all the time. Including on campus. – L

.

.

52 Comments

Alas, just handing people the book (or any book) doesn’t actually make them internalize any of the things that are actually inside the book.

You’d probably get almost as much effect for a much lower expense if you just seeded pediatrician’s waiting rooms with copies. (Sorry, Lenore, for cutting into your hypothetical royalties…)

I don’t know about most new parents, but one of the last things I was able to do was to sit down and read a book for the first 18 months after our son was born. I still have to hide myself to read a book 7 years later. Now an audio book in the car while commuting would be a far better gift and I believe your book is available on audio.

I think the best piece of information would be to stop watching TV. All the TV is telling anyone, not just new parents is there are thousands of things that MIGHT go wrong so protect your kids in every way possible. If we could stop this constant barrage of doom then we might stand a chance of bringing up normal kids who experience challenges and can make their own decisions. T

I have been instructing on a campus for a while, and I have really not had the sort of experiences with the younger generation that the press loves to put out there. I have found millennials to be, for the most part, hard working and polite. Of course not every one does well in my math courses, but most people accept their failures and move on the way every other generation probably has. Maybe the narrative of the emotionally unstable millennial is just as overblown as that of the stranger waiting to kidnap our children.

@Pophouse, thanks for sharing that comment. I do not work with college students but I manage a number of millennials and I would describe them the same way you do. I am trying to figure out if this need for emotional safety occurs mostly at highly prestigious universities or if it is everywhere. Part of me thinks this “fragile kids on campus stuff” is a matter of elite faculty talking about elite students and has no bearing on the other 98%. (Not to imply that you don’t teach at an elite college–for all I know, you do).

Lukianoff represents a religiously motivated neo-con organization, FIRE, pushing a dubious agenda. He also quotes the executive director of that org as his main source in the article you first linked to without disclosing the potential conflict of interest of that or his own relationship to said org. Vvv bad journalism that undercuts my willingness to go on their already dubious ride.

Brian,

Come on. You have to go pretty far to the left to think that FIRE is only a “a religiously motivated neo-con organization.” It’s a libertarian, free speech-focused group.

Don’t further the red/blue polarization of America by tagging everything slightly conservative with the same brush.

I’m not sure “slightly conservative” is any more accurate a description of FIRE than the one you object to.

“Haidt’s premise is that by avoiding more and more of our “fear triggers” (like, “She’ll die if she goes around the corner without me!”) we give those fears more power. They grow, and so does our kids’ anxiety.”

When we assume these arbitrary ages for which a child can and can’t do normal activities without supervision, then we also assume that with maturity, the now older child will be able to handle these activities. But the injected fear and anxiety associated with these activities doesn’t go away (because a 13 year-old going around the corner still could die) and our older kids are physically able to handle these tasks with ease, but mentally they are an absolute mess.

I know more 12 year-old girls (an age at which most kids in my generation actively babysat) with anxiety disorders who can NEVER be left alone. They do not feel safe. I don’t know how or why this fear has manifested itself inside them, but it is heartbreaking for these girls and their families.

Constant supervision is not developmentally appropriate for most children. They need to learn self-confidence, self-awareness, and develop self-esteem on their own, without the watchful and critical eyes of adults at all times. It also backfires when the child now requires and is enabled to feel safe only with this supervision. It’s not healthy for children and is leading to an explosion (at least among 12 year-old girls in our town) of mental health issues in an otherwise perfectly healthy generation

Pophouse, some of the issue is probably that you’re in the Math Department. I would expect less fragile people going into math/science/engineering as opposed to racial/gender studies, history, or other areas where one can argue into or out of a position. Math doesn’t work that way. Laws of physics laugh when faced with insipid arguments about how gravity may be racist/sexist/duplicitous/outside the gender norm. The bridge will still collapse.

@Pophouse – My brother-in-law, dean of his physical therapy department, has to regularly turn away parents who call him to protest something or other on behalf of their children.

Taking a stand in favor of the First Amendment and academic freedom now qualifies one as a right-wing nut? Yikes.

I think I’m going to go make a nice big donation to FIRE right now.

“Taking a stand in favor of the First Amendment and academic freedom now qualifies one as a right-wing nut?”

They’re partisan. The only one calling them “a right wing nut”, however, is you.

The best thing to do is stop watching TV, because all it does is tell us the thousands of things that MIGHT go wrong…..Really?

Not getting any of the above from Parks and Recreation, or The Grinder, or The Middle. I just finished watching Rectify, one of the best shows ever made in my opinion, and it didn’t really have young kids in it at all (except a group of 18-year-olds who did get into trouble). I was just thinking today about the WKRP episode “As God is my witness, I thought turkeys could fly”. I guess if something like that makes one worry about turkeys falling on your kid’s head, maybe it should be avoided, but for heavens sake it’s a sitcom.

Instead of not watching any TV, which is as valid a medium for storytelling as anything else, how about not watching the news and specific shows that give you anxiety (Law and Order: Sport Utility Vehicle, Criminal Minds, etc)?

Pophouse and Doug bring up excellent points. I’ve noticed the same patterns as a recent college grad and I really think the problem of fragile students resides within the liberal arts. Let me be clear, I’m not attacking any discipline over the others, just pointing out the trends I’ve seen. The STEM students are taught to ignore emotion and make decisions and conclusions that are backed by statistics and data, regardless of their emotions. In contrast, the L.A. students are encouraged to focus on feelings. Their feelings are reason enough to declare something to be whatever the “-ism du jour.” They don’t need any proof to back up their claims, any opinion (especially those of victimization) is equally valid no matter the data; one example being the idea that the wage gap is plain and simple sexism, the only reason women are paid less is because patriarchy. If you try to discuss nuances such as career choice, time off for children, or differences in wage negotiation, then you’re a tool of the patriarchy, too!

However, I think if college prep (whatever level that starts now: elementary, middle, or high school) put more focus on the sciences then students would be better prepared to handle the “challenges” that come with the academic arena. Even the liberal arts would benefit from the ability to think analytically instead of emotionally. Putting emphasis on analytical, fact based thinking and decision making over emotional based styles would mean that when those students become parents, they make parenting decisions based off of facts and statistics instead of fear.

Amen! I can’t stand how “bubblewrapped” this country has become. If Isis (or some other group/country/etc) were to attack us (beyond a one city attack) I have almost no doubt this country would fall, because too many people would be afraid to act, for fear of offending the attacker et al. not because this country isn’t actually strong enough to fight back.

“too many people would be afraid to act, for fear of offending the attacker”

That would be great satire… IS terrorist barges into campus building full of people in racial/gender studies, history etc etc, and before he can act, the students begin this huge discussion on whether it’s offending to him to now start running away from him because racism, or more offending when girls run because sexism, et cetera et cetera, and meanwhile he’s standing there with his bomb girdle and kalashnikov like ‘????’…

” I have almost no doubt this country would fall, because too many people would be afraid to act”

I have no idea which country you’re standing in. Not mine, because we have people who will charge armed attackers even though they themselves are unarmed.

“I’ve noticed the same patterns as a recent college grad”

May I be so bold as to inquire what your field of study was?

The world has become accustomed to seek out any possible flaw. This has it’s good points and bad points. Airplanes are designed to withstand a lose of cabin pressure. We design them to assume the worst. However this can be taken too far. When an adult sees an 8 year old without supervision then they assume a kidnapper is about to pounce. If the child is home unsupervised then it’s assumed that the house will catch fire. If a child is waiting in a car then it will be carjacked.

Seeking out flaws is ingrained so deep that people don’t even realize they do it. James is a good example of this. Although I agree with his statement, I debate the necessity to point it out and piss on your triumph. It’s common knowledge that you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink. I’m sure the author already knew this and therefore his statement….. “should come the book: Free-Range Kids by Lenore Skenazy”, was only made to state the importance of the book and not as an actual suggestion that all mothers should be given a copy.

Congratulations Lenore!

HJ,

You might want to brush up on what a liberal arts education is. You seem to think it doesn’t include science (you can be a physics major, a chemistry major, a math major in the liberal arts). Also one of its hallmarks is teaching students to think analytically, regardless of major.

@Beth

“Instead of not watching any TV, which is as valid a medium for storytelling as anything else”

You might want to look at arguments like this one:

http://onthewing.org/user/Ev_Four%20Arguments%20for%20Eliminating%20Television.pdf

The essence of television is not the content of programs, but technical events (defined in the above link).

Another study I saw said that one hour on the History Channel has as much content as half a page of an actual history book.

Pophouse, I have a liberal arts degree (albeit in chemistry). Even twenty five years ago the humanities majors were geared towards the sort of soft thinking that we see today.

” Even twenty five years ago the humanities majors were geared towards the sort of soft thinking that we see today.”

I have a 25-year-old degree in the humanities (in fact, in one of the original seven liberal arts) and… no, it wasn’t geared towards soft thinking, of any kind.

I disagree with what is being said about STEM vs. humanities education. First of all, math is not the way it’s being described: it’s a creative endeavor requiring the same sorts of skills one uses in philosophy – imagination, rigorous argument, etc. Second, deep engagement in the humanities and arguing for a position against opposition are exactly the opposite of just stating one’s opinion and avoiding argument. The humanities are precisely the opposite of anti-intellectualism, and philosophy is precisely the opposite of “you get to say whatever you feel and you’re always right.” In fact, engaging with a text and arguing about its true meaning are the opposite of snowflake power, so to speak.

Seriously? OK. How about if I watch some TV, as part of many things I enjoy doing in my free time (including reading, though I’m sure you don’t believe that), and you don’t? Thanks, but I don’t need articles telling me I’m an idiot.

@Beth – good grief, could only get halfway through that article (am nosey so and have a few minutes on my hands so took a look 🙂 )…what rubbish! Impressed if you got all the way through it.

If liberal arts is what we might term humanities (languages, sociology, anthropology, yada, yada) then the idea that they are somehow woollier in their thinking than STEM is nonsense. I did physical geography (geology, Meteorology etc) alongside English Lit and some anthropology etc, and the analytical thinking required in the anthropology, history and language-type courses was a lot more rigorous than the science courses. After all, science and math courses at the undergrad level at least are little more than fact-learning exercises.

Also, in Arts courses one cannot hide from ‘controversial’ ideas. As a conservative Christian I was often challenged in my subjects, and I enjoyed the tooing and froing of ideas. Some other students were self-described pagans, and they found the religious nature of some of the older literature a challenge too. It was the early stages of the Maori renaissance, and all sorts of discussions regarding race, the meaning of the Treaty and the way forward for us as a country were had. I remember having a ball, and being changed in some of my thinking, as was everyone in those subjects, as we analysed different viewpoints. In my STEM subjects, the facts were great, but not particularly challenging.

Great article! It is a big help to us. Also, please check this out: https://momswholefitness.clickfunnels.com/thanksgivingday-family-workout

Kids are amazing – their intelligence, creativity, and resilience. Why hide it?

FIRE is not partisan. It defended both left wing students and right wing students rights in the past and still continue to do so.

Whatever you tell parents or do in hospital delivery room has zero impact on campus politics 18 years later. There is a dynamic in campus that gives power the most aggressive and safety waving groups in expense of everybody else. Those students cry about safety, because crying about safety is what gets them what they wants. The tactics works and people wont stop using tactic that provably works.

Note how consistently ignored moderate students are. Note also that these students and faculty supporting them. What they demand is taught in intersectionality and similar courses as right thing to demand. Note also how caving to their demands changes rules in a way that gives administration/bureaucracy more power.

It does not matter how tough parents raise their kids to be. As long as decision makers are motivated to cave to aggressive overly sensitive crowd, it pays off to be overly sensitive or at least pretend to be overly sensitive.

“Second, deep engagement in the humanities and arguing for a position against opposition are exactly the opposite of just stating one’s opinion and avoiding argument.”

Sure, if that’s what they’re actually doing in universities. It’s hard to believe those Yale students are doing that, based on their public behavior. And I doubt that they’re math and physics majors, either.

Neither STEM nor humanities are magical guarantees of anything. You can teach math in a ape-like-way that requires just a little memorization and you can teach math in a way that forces students to understand, think, problem solve and be creative.

You can teach philosophy in a way that requires students to think clearly and you can teach philosophy in a way that teaches students to muddle through fuzzy definitions and promotes bad faith arguments. When philosophy course teaches theories that have no ground in reality, teacher can tell that fact to student or pretend the theory is backed by some unstated evidence.

You can teach sociology in a way that promotes science and understanding, you can teach sociology in a way that promotes pseudoscience based on misleading selection of badly designed studies. History can help us understand how world works or it can be taught it in a way that amounts to mandatory propaganda class.

The primary difference is that most of STEM is more bounded by reality then philosophy or criticism or literature analysis which practically amount to set of collected opinions and have no guarantee to be valid. Then again, not all STEM is like that.

Moreover, people expect colleges to teach values and STEM can not fully deliver that. Most of the “humanities should promote X” complains amount to precisely that – wish for humanities to promote different ideology then speaker think is taught right now. You can not have good STEM program and have it promote shared values nor anything like that – even if those values are freedom of through/speech and classical liberalism.

Yes, sure, things can be taught badly, and often are. I recently reconnected with an old philosophy professor who told me he was looking forward to retirement. In the past, he said, students had thought philosophy (and the Western Civ class he taught) was “say whatever you feel like,” but he’d been able to teach them that it wasn’t. Now, they came in thinking something different – that they already knew all the right answers, had nothing to learn from him, and anyone who expressed another opinion was evil, and often criminal. He had no problem correcting errors about what philosophy was, but this latest set of errors was impossible to correct. The good side of looking forward to retirement was that he could do what he wanted, and if he was charged with some nebulous thing and had his tenure threatened, he’d just retire. So I expect some of the bad teaching is coming from fear of what students will do to you if you teach these subjects properly, while a lot is coming from inexperienced teachers with no specific training in how to teach. The idea in philosophy is largely that of a philosopher who models what it is to be a philosopher, and a young PhD can’t really model that all that well just yet.

However, I strongly disagree with the claim that STEM is bounded by reality in a way that the humanities are not. When done well, the back and forth of argument is for the express purpose of rooting out falsehood and finding truth, which is as much reality-bound as anything. On the other hand, there is nothing stopping me, as a mathematician, from engaging in flights of fancy when creating my structures – and I do so often.

Bridge-building has a tighter connection to physical reality than humanities do – but we don’t need a society of bridge-builders. The study of subjects where there is no disagreement, and always a right answer, doesn’t seem to be a great way to teach someone to engage in reasoned, passionate arguments. In fact, every engineer I know seems convinced that, since there’s always a right answer in engineering, there must always be a right answer in everything – and, since as an engineer, there’s no need to consider opposing views, they approach disagreements on other matters the same way, and just say “no, you’re wrong,” a more mature version of the Yale girl. That’s entirely appropriate in an engineering context, but not when discussing political issues.

I agree there’s no magic bullet, which is why an ideal liberal curriculum includes humanities and sciences. Let’s not judge the humanities by those who do them poorly, though.

Also, the girl’s behavior tells us absolutely nothing about what is being taught. We don’t even know if she goes to class, and if she does, she could well not pay attention, sitting in her bubble of rightness, then later complaining that the professor offended her.

It is a mistake to hold up engineering in general, or even bridge-building in specific, as an example of an area where there is one right answer and all the rest are wrong. First off, just as is the case with science, the current state of the art is only an approximation of reality. Usually, that approximation is correct. Sometimes, it isn’t, and some undiscovered effect displays itself with disastrous results. A bridge that is designed without an understanding of harmonics collapses in high winds.( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-zczJXSxnw ) A bridge that assumes that strength-of-materials is a constant fails when the metal fatigues.

Some people can tolerate more ambiguity and uncertainty than others. I think this affects what fields of endeavor they will tend to be drawn to. People point (incorrectly) to mathematics as a field where there is one right answers and all the rest are wrong. The people who do so have a poor understanding of mathematics. Sure, at the grade-school level, arithmetic works that way. But… what is the square root of 4? More importantly, how many square roots of 4 are there? By the time you get to integral calculus, every problem has an infinite number of solutions. (The way to account for those infinite solutions is to not forget to add ” + C ” to your answer. Note that integral calculus produces meaningful results despite the fact that it produces an infinite number of correct answers.)

People who want certainty gravitate to theology, where the conclusive answer to any question is “because God said so, that’s why!” Oddly, this doesn’t mean that they have nothing to argue about.

It is amusing to see people talking about entire fields of study as if everyone in them all thinks the same way, or who look at all college students as if they are alike.

“When done well, the back and forth of argument is for the express purpose of rooting out falsehood and finding truth, which is as much reality-bound as anything.”

I disagree on back and forth being reality bounded, at least in a sense how I meant it. It is opinions bounded. Back and forth does not fact check. It is very easy to introduce misleading semi-truths into back and forth (especially semi truths about history). Pure back and forth tend to lead to nice theories that are in odds with how world works.

Back and forth can root out falsehoods only when participants double check things being said with something measurable – but that is step where you are going out of humanities and into statics and science. Immediate in class back and forth is good exercise, but also limited to what you all remember right now, sensitive to shared (or teachers) bias and glosses over anything complicated that requires a lot of concentration and thinking.

While you can flight with math structures themselves, that just makes them useless but not unbounded. Your structures are still bounded by axioms you have chosen and you still need to prove whatever you plan to claim about those structures. More importantly, wild math structures does not pretend to say things about real world and have no power to change anyone opinion or attitude about anything real world. Which makes them harmless (and useless).

“since there’s always a right answer in engineering”

That is not truth. There is not always right answer in engineering and even if there is, it is often hard to determine. Plus, it is not true that just saying “that is not true” is enough to win in engineering – especially in any developing discipline. You need to back that opinion with something, definitely so in math, physics and computer science related world.

There is more variety among engineers I know, so all engineers you know being pretty much the same is weird. It might be just feature of your close social circle or something like that. It is too much sweeping, just like the claim that all artists drink too much. I might buy “more then elsewhere” or even “majority”, but “all of them” is too suspicious. Frankly, it sounds like one of those things that tend to be accepted in back and forths, but rarely confirmed when someone actually does personality or psychological tests.

“I agree there’s no magic bullet, which is why an ideal liberal curriculum includes humanities and sciences. Let’s not judge the humanities by those who do them poorly, though.”

I think that in ideal world, we would decide what is the goal of college first and what the outcome should be like (just signal to employer about students persistence and character? certificate that they have defined set of skills? which set of skills?) and design curriculum second. It seem to me that people who participate in these discussion have very different ideas about what the goal is in the first place.

“I disagree on back and forth being reality bounded, at least in a sense how I meant it. It is opinions bounded. Back and forth does not fact check.”

The American legal system is based on the premise that an adversarial process is the best method for finding truth. It’s not perfect, mind you, and can be manipulated by people with power, but no system of thought is free of that.

Science is built by a process of back-and-forth, as well… that’s why credit for discoveries goes to the first person to publish. The important part of discovery isn’t finding something, it’s sharing it with others.

“I think that in ideal world, we would decide what is the goal of college first ”

The first goal of a university is research. Education is a side product.

@James Pollock “The American legal system is based on the premise that an adversarial process is the best method for finding truth.”

Highly procedural adversarial process of American legal system is super far from in class philosophy back and forth. And it is no magical “get truth” device, it is “cancel out procurator/defense” biases device. It is “minimize corruption” device. It just happen to be badly suited to decide what is better science as all scandals around forensic not-exactly-science shows.

I am not saying other legal systems are much better comparatively, before someone gets defensive. I am saying that it is method of making decision out of contradictory statements and available evidence within reasonable time. It is decision making process.

Just like democracy best is decision making process we have available, democratic discussion is not method of building science or necessary finding the truth.

“Science is built by a process of back-and-forth, as well… that’s why credit for discoveries goes to the first person to publish. The important part of discovery isn’t finding something, it’s sharing it with others.”

Ugh. Scientific process is supposed to be more then just people discussing and doing back and forth. Peer review is not back and forth, it is different verification process – or at least supposed to be. When peer review process descent into loose back and forth without all that evidence/hypothesis stuff, than you can expect scandals about non-valid science without ten or so years. There is a lot of “get back to measure some more date” in scientific process and there is a lot of “we do not know” in scientific process.

Who gets credit has nothing to do with topic.

“Scientific process is supposed to be more then just people discussing and doing back and forth.”

Who has a better theory, scientist A or scientist B? This will be decided by various scientists examining both, and bringing in observations, tests, and more theories. Ultimately, the better theory is the one that can be used to make accurate predictions about future observations. Even the most established theories are subject to being displaced by better ones, if they can be used to make accurate predictions. Aristotle was right until he wasn’t, Newton was right until he wasn’t, Einstein was right until he wasn’t.

Science is about repeatability (can other scientists replicate your results). And it’s about building all the different pieces together, building on the work of the science that was done before you came along to add your piece. So it’s also about other scientists taking your work and attempting to apply it in ways that you didn’t.

Science stops dead when people stop discussing things back and forth.

James said one thing I disagree with, and several things I agree with and won’t repeat. In response to the first point James made to my post: of course I’m aware that mathematics is more than seeking out “the answer” or performing a set of skills. I said as much just a few posts above, and it so happens that I’m a research mathematician. Granted, my bridge-building statement was overblown – but it was in response to a claim that STEM is reality-bound and that this boundedness is always and everywhere a feature.

Now to Andy: Yes, I am bound by my axioms, but I am bound by nothing when I come up with those axioms, except possibly when I’m trying to study a particular pattern. The notion that pure mathematics is therefore useless is rather absurd – the whole point is as a mental exercise, and to create beauty, in this case beautiful patterns. On a practical level, it very often emerges that the most abstract structures, those we imagine have no use, turn out to have important applications decades or centuries after they are first used.

You say “back and forth does not fact check.” That’s just not true, especially when one party to that back and forth happens to be an expert scholar. This is my point – philosophical discussion, or interpretation of texts, is not simply “spew out what sounds right to you and then argue for it.” In a good back and forth, you go to the texts, you bring proofs of your claims, you reference facts, you rely on both perceptions and intuitions.

There seems to be some idea that there is a capital-T Truth which discussions may or may not miss. In reality, we are doing exactly what you suggest – trying our best to figure it out. There is no perfect form of study. This is baked into the scientific method as much as it is into our humanities inquiries, which is why science rests on falsification, not confirmation.

As for legal argument (the better examples here are probably appellate oral arguments, so I’ll just look at those) being entirely different from what goes on in a philosophy class – not really, at least not in a good philosophy class. I’ve been in a few philosophy classes that have fallen into bull sessions, so I see where you’re coming from, but I’ve also had the experience of taking classes with great philosophers who tolerate nonsense no more patiently than Antonin Scalia. They lecture, then they engage the class – and jump eagerly on any error, misstatement, or misstep, exactly the way a judge will during oral arguments. They insist at all times on clarity of meaning, and will destroy you if, as often happens, you don’t know what you’re saying. You emerge shaken, but with a far greater appreciation for what the pursuit of truth means and doesn’t mean.

“James said one thing I disagree with, and several things I agree with and won’t repeat. In response to the first point James made to my post”

I’m having trouble figuring out what the one thing is. Perhaps because I haven’t made a response to your post. In any case, I think we are arguing the same side of the argument.

@Puzzled I did not said nor meant that mathematics is useless.

However, philosophy is not about getting to truth in the same sense as science is. The texts you go back to are someones opinions and ideologies. Opinions of smart people, sure. They are backed by some experience, they are interesting fun or challenging ideas, but in the end of day they are opinions without statistical or experimental backing. It is not search for truth in the same sense as science is supposed to be. Of course it is partly because it tends to deal with questions that science can never answer (those related to values), but that does not make them less of sophisticated opinions systems and ideologies.

As for legal, afaik, American appellate oral arguments are supposed to be process based, they do not re-evaluate evidence, they check whether all ts were crossed. At least that was my understanding of American system. They can reopen the process.

The general court is expected to answer one question “is this enough evidence to conclude without doubt that the person is guilty”. They are not equipped to answer scientific questions. They just hope invited experts get it right and when experts disagree, they make their best guess.

The jumping on missteps is cool and useful thing of course, but that does not change the fact that philosophies inherently boils down to elaborate value systems. Sometimes despicable systems with horrible real world consequences. Alright, sometimes good.

When I say they can get unbounded from reality, I mean exactly the situations where the “cultural appropriation” theory is suddenly used to to protest things original culture wants to export. Or when death of author paradigm is used to label non American entertainment racist, cause it does not reflect American society racial split or problems. Author intent does not matter, a lot of logically sounding words, and suddenly you have situation in which whole world is expected not to create art based on their own histories. That is not made up example, there was a lot of loud noises made against Polish game that happen to be based on popular locally writer. That was when I learned about critical analysis first time and it made quite bad impression on me.

“However, philosophy is not about getting to truth in the same sense as science is.”

The original name for what we now call “scientists” is “natural philosophers”. There’s a reason why the highest academic achievement in the sciences is a “PhD”.

(BTW, strictly speaking, science is not about finding truth. It’s about finding the closest approximation. Truth is an endpoint, and science, by its very terms, never claims to attain it. All you get with science is “the best we have now”. If you want capital-T Truth, you need to exist the science building, and pop over to the Theology department… that’s what they sell.)

“The general court is expected to answer one question “is this enough evidence to conclude without doubt that the person is guilty”.”

Sorry, you want CRIMINAL court, that’s next door. Here we have CIVIL court. We’re trying to determine “does a contract exist, and if so, what are its terms?” This afternoon we’ll be playing a rousing game of “what are the best interests of the children?”

“when experts disagree, they make their best guess. ”

By amazing coincidence, this is how scientists do it, too.

James Pollock While origins of names are interesting historical trivia, they are hardly an argument for anything except the history of the word.

If you meant civil court only, you should have say so. And again, the conflict resolution of civil court is not about “finding truth” – you used the word in this relation first. They are about making decision out of known facts. And yet again, this has so little to do with philosophy or science, that you might as well argue by the best gardening practices.

“By amazing coincidence, this is how scientists do it, too.”

No, they do not. And when they do, we call it scientific fraud.

Unless you want to deny that abuses of science exist, it doesn’t help much to point to abuses of other fields to establish your point.

Again, you’re relying on the implicit premise that science actually has some tool to find a real truth, instead of doing exactly what you’ve described. How do scientists investigate each other’s work? Well, they study the methodology and challenge it – the way you describe appeals courts. They repeat the experiment. They say “we have failed to falsify these results” and see if future research changes anything.

Sure, the texts are full of one person’s writing (not entirely their “opinion” unless you want to make everything an opinion), but the text itself is real and has a real meaning. Books are not entities exempted from reality. What we’re doing when we study philosophy is getting at the truth about the text. Again, yes, a poor philosophy class can collapse into “and what do you think about this idea?” but so can a poor science class.

On the other hand, a person doing philosophy proper is precisely trying to understand some aspect of the world. Others will accept or reject their theory based on how well it comports with reality. If you have the illusion of science as being “absolutely true” this will seem softer, sure.

On appeal – there are other issues discussed aside from judicial process. Yes, that is a common argument, but appeals courts can also hear (if it was included in the argument at trial) arguments about Constitutionality and claims of mistakes of law – which can only be decided by deciding what the law is. You might find it interesting to spend some time with the podcast Oyez, which contains oral argument presented before the Supreme Court.

“Unless you want to deny that abuses of science exist, it doesn’t help much to point to abuses of other fields to establish your point.”

I was not talking about abuse of philosophy of some humanities. What I meant was that they extrapolate opinions from opinions to get more and more complicated systems, but there is not much more in that. As long as we see that as interesting challenging exercise about values or whatever without too important meaning, it is fine and I like the game.

Once we start to make real world conclusions from those extrapolations, I have a problem with that. To use analogy, when you create sorta kinda but not exactly mathematical model from word, make math theory, the results might or might not map back to real world. Math tend to be aware of that and mathematicians I know do not claim theories map real world perfectly, although it is easy to use to mislead. That is why experiment is so important in physics, because you can not trust the math model gives correct results if you did not tested its real world application.

Philosophy tend to be less aware of that and like to pretend their stream of extrapolations was not just that. It is not question of misuse, it is question of not having an equivalent of an experiment in the first place. It has not in built feedback mechanism in which real world can say “nope you went wrong somewhere”.

“Again, you’re relying on the implicit premise that science actually has some tool to find a real truth, instead of doing exactly what you’ve described.”

I am mostly saying that I disagree with notion that philosophy is about finding truth. That should not have implications about science being always totally accurate. Mental models coming out of philosophy can be right or wrong, truth or false, and there is no way to know nor ever will be.

“How do scientists investigate each other’s work? Well, they study the methodology and challenge it — the way you describe appeals courts. They repeat the experiment. They say “we have failed to falsify these results” and see if future research changes anything.”

I agree that challenging and verifying each other work is important.

“Sure, the texts are full of one person’s writing (not entirely their “opinion” unless you want to make everything an opinion), but the text itself is real and has a real meaning. Books are not entities exempted from reality. What we’re doing when we study philosophy is getting at the truth about the text.”

Sure, they are things writer really wanted to say, either because he thought so or to manipulate us.

“Again, yes, a poor philosophy class can collapse into “and what do you think about this idea?” but so can a poor science class.”

I expect science to be more then just mental exercise. We could teach puzzle games instead of math for that. Instead, we teach math because some students might need math to understand courses later on or even need it in work. We teach biology not just as exercise about experiments, but to teach them biology as known so far because we expect them to need it later on.

“On the other hand, a person doing philosophy proper is precisely trying to understand some aspect of the world. Others will accept or reject their theory based on how well it comports with reality. If you have the illusion of science as being “absolutely true” this will seem softer, sure.”

It is mostly that topics are different. This understanding of world is more about values and about the fact that humans want the sense of understanding world where “hard” facts are unavailable – we make up answers because feeling that “we do not know” feels bad for many people.

“I expect science to be more then just mental exercise.”

What, exactly, is it you expect?

Science and the sciences are often taught as collections of facts to learn, rather than as a process. Never mind what we think we know… “WHY do we think that is how the universe works?” is the important part of science.

I expect engineering to have real-world application. Science, on the other hand, is just attempting to explain why we observe what we do. The classical Greeks had a disdain for experimentation… getting one’s hands dirty is the job of a slave, not a natural philosopher… which is how you wind up with the seven liberal arts in the first place… none of them expected to have real-world application… they’re exercises of the mind, suitable only for free men (that is, people who have leisure time for this sort of thing, and don’t have to, you know, have anything to show for the effort.

Stop applauding every time they have a good bowel movement.

@James Pollock Yep, it totally makes sense to argue by classical Greeks lifestyle in debate about 21 century philosophy and science. It is not like things would evolve and change meanings over two thousands years.

To answer your question, I expect school science to teach physics, biology, statistics, chemistry. Have curriculum which defines how much time is spend by newton laws, how much by relativity and how much by electricity. I expect biology to teach immune system or observed behavior of animal. I do not expect college to teach general “science” the way elementary schools teach little kids. Even high schools are above that and teach physics, biology, math and chemistry separately.

And yes, topic and facts are important part of the whole thing, as much as the process.

“Yep, it totally makes sense to argue by classical Greeks lifestyle in debate about 21 century philosophy and science. It is not like things would evolve and change meanings over two thousands years.”

2500 years, but who’s counting? (Way to miss the point, BTW)

“I expect school science to teach physics, biology, statistics, chemistry.”

Statistics is math, not science. And you left out rather more than a few of the sciences.

“I do not expect college to teach general “science” the way elementary schools teach little kids.”

To whom? To people who’ve come to college to study “science”, or to people who’ve come to college to study something else? Most colleges don’t require calculus-level math to graduate. Physics needs calculus (which is why Newton had to invent it.) So right off the bat, most college students are blocked out of even basic Mechanics, much less any of the physics of the last century…. unless you teach Physics in two tracks… generally referred to as “Physics with calculus” and “Physics for Liberal Arts majors”. Chemistry has a similar, though less stark problem…(especially since chemistry is just a special field of physics) Biology is OK, if you leave out the biochemistry, as most biology courses do (except, of course, for the ones with “biochemistry” in the name.)

The end result is that most people take science classes that, yes, are taught the way that little kids are taught science… because otherwise, they’ll take no science at all. And, there’s an argument that this is proper. People who buy education should have a say in what they buy (and pay for), rather than have somebody say “no, you have to learn this, too.” While science affects our lives, very few people actually need a strong understanding of it. I don’t need to know the chemistry of gasoline combustion or the physics of expanding gases to operate my truck. I need to know that the long skinny pedal means “go” and the short square one means “stop”. The engineer who designs them better have an understanding of the science, but most of the rest of us don’t have to.

I think it would be easy to pick out the people in any generation who appear to have difficulty coping, but using those few examples to make a generalization about everyone in that cohort is a mistake. Every generation thinks they’re tougher than the one who follows. Ask those who survived World War II and the Great Depression what they think of baby boomers.